Brielle Ferguson, Ph.D.

Postdoctoral Fellow

Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences

Stanford University

Developing resiliency to overcome obstacles

Before I started college, I didn’t have much exposure to higher education in the sciences. I had a really limited idea of what careers were possible for me, so as an undergraduate at the University of Virginia, I decided to pursue the pre-med track. Early on, I struggled academically with some of my science courses. Looking back, I think part of why I lost interest in these courses is because I just lacked context on why they were important or why I needed them for my career. I needed to take a step back to think through my options. I considered psychology since I enjoyed the coursework but working in a psychology lab made me want to delve even deeper into the brain. Through my cognitive science major, I gained a deeper understanding of neuroscience and just fell in love with it. After volunteering in a neuroscience research lab, I knew I wanted to pursue a PhD in Neuroscience and I was ready. However, convincing graduate schools was another story.

Graduate admissions committees worried I would struggle with graduate school given my grades from my earlier science courses. However, I had done well in all my neuroscience courses later in my undergraduate studies, so I knew I could hold my own. I applied to six Neuroscience Graduate Programs and was accepted to one, Drexel University. I really had to advocate for myself during the admissions process. When applying to graduate schools, I reached out to potential laboratories and connected with researchers at Drexel that I wanted to work with. After a few conversations with my future doctoral advisor, I was able to secure an interview and demonstrate my passion and knowledge for neuroscience.

At Drexel, I joined the lab of Dr. Wen-Jun Gao, exploring how the mediodorsal thalamus regulates the prefrontal cortex to impact cognition. While I did well in my graduate coursework, it was initially difficult for me to get my research projects off the ground. Life as a researcher can be incredibly challenging. For one, the output of your work is not necessarily proportional to your input. You can work meticulously and tirelessly to collect your data, but still, experiments may not work as you planned, or hypotheses might not pan out. I struggled to get my dissertation experiments going, then even once I did, it was difficult to get funding for my research or to publish my research. It was a disheartening time for me, but I realized that this was all part of the job and I learned to become more resilient. In research, you are constantly faced with obstacles, so to me, resiliency is one of the most important skill researchers need to develop.

During graduate school, I applied for a NIH F31 award three times. Each resubmission felt frustrating in the moment, but it was actually a great learning experience for me. I became a better grant writer each time and I learned how to productively respond to reviewers. I continued to apply after each rejection because I knew the F31 award was a great opportunity to strengthen my professional development. And my persistence paid off; once I got the award, I was able to enroll in a workshop at Cold Harbor Spring and attend several scientific conferences, such as Society for Neuroscience, to enhance my professional network.

Another challenge I encountered during graduate school was the lack of Black representation in my community and the field more broadly. At first, I didn’t even realize how much it affected me until I saw a Black faculty member give a talk for the first time during my fifth year of graduate school. Seeing them speak about their research made me realize both how much I had been missing seeing examples of Black success stories in academia and also that becoming a faculty member was an attainable goal for me. Graduate programs are making an effort to try and recruit more diverse trainees, but at the faculty level, it’s still rare to see a Black faculty member at research institutions, so there’s a lot of work still to do. That’s why the work I do as Programs Director of Black In Neuro is so near and dear to my heart. Part of our mission is to increase the visibility of Black neuroscientists at every level. I hope that most people won’t have to feel this problem as acutely as I did and that at the least knowing Black faculty exist will become less of a hurdle for other trainees.

As I was wrapping up my graduate work, I met my current postdoctoral advisor, Dr. John Huguenard, at the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students (ABRCMS) Meeting. There was quite a bit of overlap in the circuits we were interested in, but his lab studied them in the context of epilepsy rather than cognition. I joined the Huguenard lab because I knew it would challenge me intellectually, teach me novel techniques, and provide me an opportunity for growth. I received an NINDS F32 award during this postdoctoral experience. This award does not require preliminary data, so I was able to secure funding early on during my postdoctoral career to support my research, which gave me the flexibility to pursue bigger research questions leading to more exciting results. Again, the funding gave me the ability to travel to several scientific conferences, such as the American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting, the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology Annual Meeting, and Gordon Research Conferences. Overall, this funding helped me expand my professional network and provided exposure for my research. I started to receive invitations to speak at conferences and seminars, like the Intersections Science Fellows Symposium. The ability to share my work and receive insightful questions and feedback as I prepared to apply for the BRAIN Initiative K99/R00 award were invaluable in helping me receive this grant. Additionally, it really helped me fine-tune my hypothesis and build my confidence for the academic job market.

As you go through your career as a researcher, remember that all the failure and rejection you face is not real failure. If you don’t get your grant funded or your paper doesn’t get accepted, try not to take it personally and try again. Even though it feels frustrating in the moment, it will help you fine-tune your ideas, and it will make you stronger and sharper. These moments make you a better scientist. When you do encounter failure, you don’t have to process it alone. Surround yourself with a strong support system. My doctoral and postdoctoral advisors have both been incredibly supportive and responsive to my scientific and mentorship needs as a trainee. They both ensure that their trainees have the necessary support, tools, and resources to succeed in their academic careers. Finally, never forget how incredible it is that you’ve made it to where you are now. We can get so caught up in the grind and focus on everything that’s difficult or has gone wrong in the lab, but we forget that very few people in the world even pursue a Ph.D. You just existing in the space you’re in, no matter your career stage, is magical and you can’t lose sight of that.

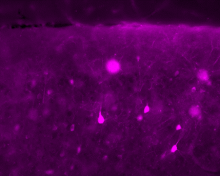

Current Research

My primary research focus is understanding how interneuron subtypes support attention and contribute to attention impairments across disease states. I use an attention task I developed as a postdoc that can capture behavior differences in multiple genetic models of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. With this task, I have begun to identify markers of successful and dysfunctional attention that I am eager to characterize with a battery of systems neuroscience tools. In my future lab, I hope I can identify therapeutic targets for treating patient populations with treatment-resistant cognitive impairments. The Ferguson Lab will open in early 2023 at Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School.